1.

Denis Wood makes weird maps – maps of the shadows leaves leave on the ground, of the pools of light spread by streetlamps, of the sounds of wind chimes in his neighborhood.

His book, Everything Sings, is an attempt to work through what it means to live where he does the way he does; to, in a sense, build an atlas of his own life.

The idea is that maps are invariably made for purposes. There are maps of streets, of flight paths, electrical pylons, home prices, sewers, river systems, trail systems, language, race, income, wind, stars, the ocean floor… Most maps probably wouldn’t be much use to anyone but the very small audience for whom they’re made. As I write this – or, the first time I wrote this, sitting on an airplane – I am looking at at topological subway map, where the distances between stops is utterly inaccurate, but this is fine, because they’re also utterly unimportant. All that matters is the order of stops and connections between lines. The space doesn’t matter. As Wood puts it elsewhere, in an earlier academic work, maps aim to facilitate certain types of living by grappling with “what is known instead of what is merely seen.”

Maps work by only telling you a small part of the story – by sorting out, from the world’s blooming buzzing confusion, some small thing made meaningful by what you’re trying to do. But what’s meaningful for the business of living? Wood’s answer seems to be that lives are made up of the small things we usually overlook – pumpkin faces and street lights.

2.

Years ago I went through a phase of drawing maps, but I could never get it right. I drew every corner as a right angle, but every corner isn’t a right angle, and there are only so many right angles that you can impose on the world before you end up running two streets together that don’t run together. When my streets irrevocably collided, I’d draw a squiggle, indicating, I’d always swear, more detail than could be covered in a map that size.

My maps were still good for some things. If you wanted to know, say, how to get to Jenny’s house from mine, they could tell you: take your first right to go into the woods, go straight at the four way trail intersection, turn right again at the field, and the house will be there. Provided that you didn’t want to go anywhere complicated, they were fine for directions. It’s just that the way they represented space had nothing to do with the world.

It’s not just that I drew space wrong. I knew it wrong too. I would get into arguments with my friends, the sorts of arguments I imagine young boys always get into, trying to show who is better at being in the world. When someone disagreed with my directions, I’d draw a map in the dirt – again, all right angles – as though, by drawing it, I somehow made it real.

3.

From Borges’s short story, “On Exactitude in Science”:

In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography.

4.

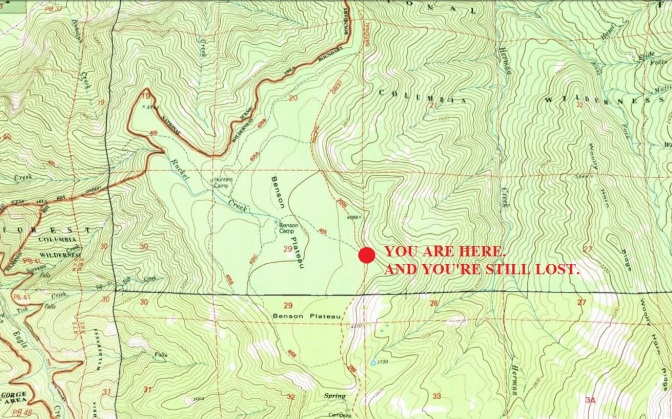

The most scared I’ve ever been hiking was up in the snow on the Benson Plateau last spring. I’d walked up from Eagle Creek with the plan of taking Benson Way across the Plateau to Ruckel Creek, and Ruckel Creek back down to the car. But once I got to the Plateau, all of the trails were covered in enough snow that I couldn’t follow any of them except for the well-worn PCT.

I came to a signed trail junction, and turned left to head toward Ruckel Creek. No dice. I lost the trail within twenty feet. Back at the junction, I looked at my map. I knew exactly where I was, but had no idea how to get home.

The worst case scenario was that I’d just follow the PCT to Bridge of the Gods, then walk back a couple miles along I84 to Eagle Creek. Not ideal, but definitely better than spending the night lost in the snow.

But see, I’m stubborn. So I kept trying to follow game trails or real trails or I don’t even know what toward Ruckel Creek. But then, inevitably, I’d get lost – or, maybe I should say, I got lost in the new way. It became an almost comfortable pattern.

It wasn’t until the last possible trail that I found a light pair of snow shoe tracks from someone a few days before leading where I wanted to go. They got obscure a few times, but, compared to the last few hours, it was just a little wandering. After maybe a mile and a half, I reached Ruckel Creek and a trail I knew. I sat down immediately for a very late, very triumphant lunch. I didn’t even have to look at the map to know where I was.